> Adlerwerke Historical Site (Foyer)

> A crime that became a part of everyday life

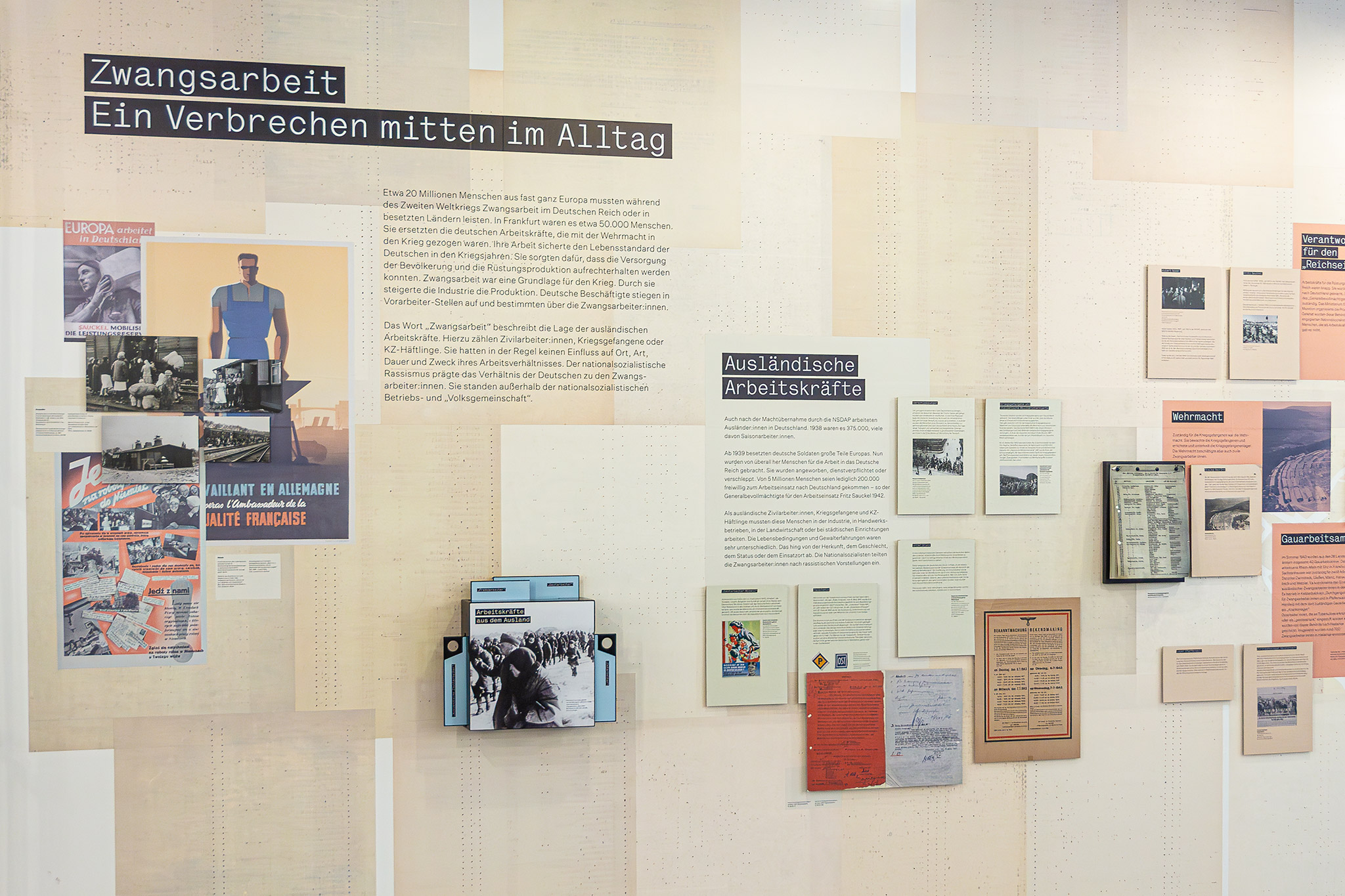

> Zwangsarbeit – ein Verbrechen mitten im Alltag

> The forced labour system

> System Zwangsarbeit

> The concentration camp in the factory

> Das Konzentrationslager in der Fabrik

> Clearance and death march

> Räumung und Todesmarsch

> Conflicts over labour, remembrance, compensation

> Konflikte um Arbeit, Erinnerung, Entschädigung

A crime that became

a part of everyday life

During World War II, some 20 million persons from nearly all over Europe had to perform forced labour in the German Reich or in occupied countries. In Frankfurt there were about 50,000 forced labourers. They replaced the German workers who had been called up for military service in the Wehrmacht. Their work guaranteed the living standards of the Germans during the war years. It was thanks to them that the people could be provided for and armaments production maintained. Forced labour was one of the foundations of the war. With it, the industry was able to increase production. German employees were promoted to foreman positions and put in charge of the forced labourers.

The term “forced labour” describes the situation of foreign workers, whether civilians, prisoners of war, or concentration camp inmates. They generally had no say in the location of their workplace, the type of work they were assigned to, or the duration or purpose of their employment. Nazi racism defined the Germans’ relationship to the forced labourers. The latter had no place in the National Socialist industrial or “people’s” community.

Theme box: Manpower from abroad

Manpower from abroad

Arbeitskräfte aus dem Ausland

“Alien workers”

In the Nazi period, the Germans used the term “Fremdarbeiter”—“alien workers”—to refer to civilian foreign workers. In the post-war era, the term served to obscure the involuntary nature of many employment relationships between 1939 and 1945.

“Guest workers”

The term “guest workers” was rarely heard in the Nazi period. Starting in the 1960s it was used to refer to migrant workers. The German authorities assumed that they would remain in Germany for only a limited time. “Guest worker” was considered a friendlier term than “alien worker”. There was also an effort to avoid any association with the history of forced labour.

“Foreign civilian workers”

During the Nazi period, the administration referred to forced labourers employed by civilian companies or government agencies as “foreign civilian workers”. The use of this term made it unclear whether the workers were employed voluntarily or by force. In the early phase of the war, foreign civilian workers were recruited on a voluntary basis. As the fighting continued, the conditions for foreign workers worsened radically.

“Eastern workers”

The Nazi administration used the term “Eastern workers” primarily to refer to forced labourers from the countries of the Soviet Union. Starting in 1941, entire groups of persons born in a certain year were conscripted at once and transported to the German Reich. From 1942 onwards, “Eastern workers” had to wear a badge with the letters “OST” (east) on their clothing. According to Nazi race theory they made up the lowest rank. Only persons persecuted as Jews or “Zigeuner” (derogatory term for Sinti and Roma) ranked lower. Special laws that went into force in 1942 robbed the “Eastern workers” of nearly all their rights.

Deportation from Jankowo station in Poland to Germany for forced labour

Propaganda photo, March 1943

German Federal Archives, image 183-J22099, photo: Krombach

Foreign workers

Foreign workers

Ausländische Arbeitskräfte

There had also been foreigners working in Germany between 1933, when the NSDAP (Nazi party) came into power, and 1939. In 1938 they numbered 375,000; many of them were seasonal labourers.

Starting in 1939, German soldiers occupied large areas of Europe. Now people were brought from far and wide to perform labour in the German Reich. They were recruited, conscripted, or deported. Of the five million who came, only 200,000 did so voluntarily—according to Fritz Sauckel, the General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment, in 1942.

Bearing the status of foreign civilian workers, prisoners of war, or concentration camp inmates, these persons were assigned to labour in industry, the trades, agriculture, and municipal institutions. Their living conditions and whether or not they were subjected to violence differed widely depending on where they were from, their gender, status, and place of work. The Nazis deployed them for forced labour based on racist principles.

The “guest worker model”

The “guest worker model”

„Gastarbeiter-Modell“

Workers from Italy (until its capitulation in 1943), Croatia, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Romania came to Germany voluntarily. The German Reich was allied with these countries. People were lured to sign up for labour service by recruitment agencies in the cities and Sunday advertising campaigns in the countryside. Often more promises were made than kept. After signing contracts, the people were transported to Germany on special trains.

There were also recruitment agencies in the occupied Netherlands.

“Prosperity in your family through work in Germany!

Sign up at the regional employment offices.”

NIOD, beeldbankwo2, no. 193513

Racism

Racism

Rassismus

Persons from the Soviet Union and Poland were subject to especially harsh discrimination. In the “Polish decrees” issued on 8 March 1940, the regime introduced the first badge requirement for the purpose of ostracizing a group of the population, the “P” badge. The yellow star for Jews followed in 1941, a year later the “OST” badge. The “Eastern worker decrees” of 20 February 1942 provided an administrative framework for the exploitation, discrimination, and ostracism of over two million Eastern workers. Labourers from Poland and the Soviet Union received fewer rations than Germans and other foreigners. A special tax was imposed on their meagre wages. They were not permitted to leave the town or village where they worked. The Gestapo had the authority to commit them directly to a “work education” or concentration camp. They were not permitted to use public transport or bicycles, go to restaurants or pubs with Germans, or attend worship services. They were forbidden to cultivate private contact of any kind to Germans. Sexual contact to women frequently ended with concentration camp imprisonment for the woman and a death sentence for the man.

Badge for Polish forced labourers

Dokumentationszentrum NS-Zwangsarbeit / Collection Berliner Geschichtswerkstatt

Badge for “Eastern workers”

Dokumentationszentrum NS-Zwangsarbeit

Under pressure

Under pressure

Unter Druck

In the areas occupied militarily, the German authorities initially tried to attract workers through advertising and promises. For the most part, however, Western Europeans were unwilling to go to Germany to work.

The Germans therefore began to increase the pressure. In Poland, the occupied territories of Western Europe, and the Soviet Union, the German administrations brought industrial operations to a standstill. They prevented the supply of pre-products or ordered the factory’s shutdown. The workers lost their jobs. Those who failed to register with the employment office risked the reduction or deprivation of food stamps and social security benefits. Many of the unemployed were conscripted for labour service in Germany.

As a result, many younger persons, mostly single, registered for labour deployment, even if it meant being sent to Germany.

There was resistance against conscription for labour service in Germany.

The German occupiers reacted to the theft of index cards for the registration of workers by imposing curfews and re-registering all men born between 1917 and 1924.

Prisoners of war

Prisoners of war

Kriegsgefangene und italienische Militärinternierte

Thousands of foreign soldiers were sent to Germany as prisoners of war. Those of them fit to work were hired out to businesses and companies by the employment offices.

This was initially the procedure for Soviet prisoners of war. The Wehrmacht treated persons from Eastern Europe differently for racist reasons. During the initial months of the Eastern Campaign, the German Reich let some two million Soviet prisoners of war starve to death. It was only after the German advance came to a standstill in late October 1941 that they were deported to the German Reich for labour service.

Italy ended its collaboration with the Nazi regime on 8 September 1943. In response, the Wehrmacht deported some 600,000 Italian soldiers to the German Reich and occupied areas to work. As “Italian military internees” (IMI) they were denied the protection granted prisoners of war under international law. The armaments industry profited from this new manpower. Tens of thousands of them lost their lives to hunger, forced labour, disease, and bombing attacks.

Arrival of the first Polish prisoners of war at Ziegenhain station, from there they proceeded to the Ziegenhain POW camp on foot, September 1939

Gedenkstätte und Museum Trutzhain

Deportation

Deportation

Verschleppungen

In order to bring enough manpower to Germany, the German occupiers increased the pressure: Entire groups of persons born in a certain year were conscripted at once. In many regions the German authorities stipulated the number of workers to be recruited and the local administration was assigned to select them. Elsewhere, people were rounded up at assembly points and deported to Germany. The Polish and Soviet forced labourers were transported in closed goods waggons. The journey took several days during which they had nothing but a bucket in the corner of the waggon in which to relieve themselves.

Raid in Rotterdam: On 10 and 11 November 1944 more than 50,000 men between the ages of 16 and 40 were arrested in Rotterdam and deported to eastern Holland and the German Reich to perform forced labour.

NIOD, beeldbankwo2, no. 83431, photo: H.C.L. van der Werff – Burwinkel