> Adlerwerke Historical Site (Foyer)

> A crime that became a part of everyday life

> Zwangsarbeit – ein Verbrechen mitten im Alltag

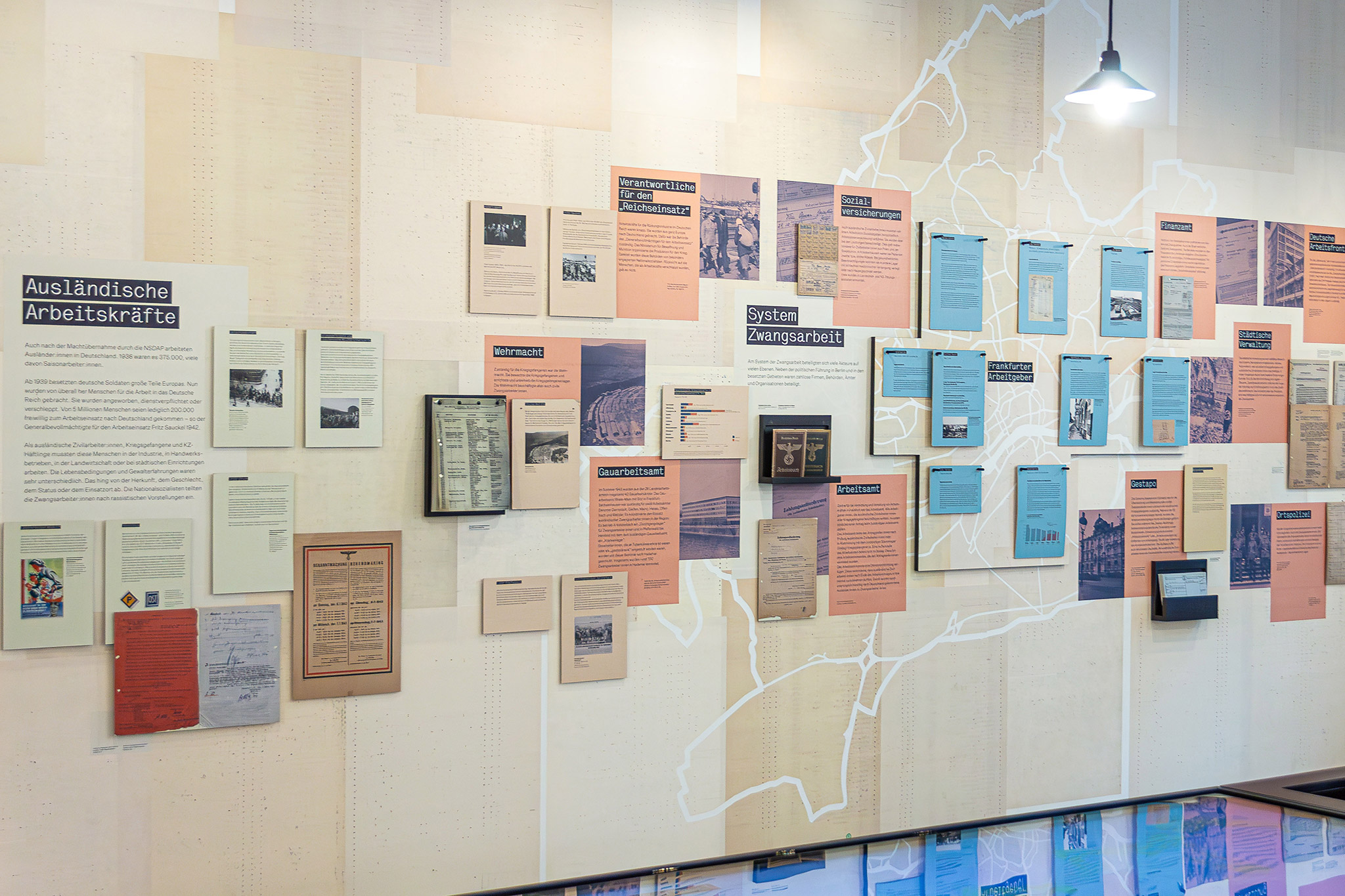

> The forced labour system

> System Zwangsarbeit

> The concentration camp in the factory

> Das Konzentrationslager in der Fabrik

> Clearance and death march

> Räumung und Todesmarsch

> Conflicts over labour, remembrance, compensation

> Konflikte um Arbeit, Erinnerung, Entschädigung

The forced labor system

There was a shortage of manpower for the armaments industry in the German Reich. Workers were brought to Germany from all over Europe. The government agency responsible was the office of the “General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment”.

The Ministry of Armament and Munitions organized production for the war. These agencies were headed by especially dedicated National Socialists. There was no such thing as concern for the persons deported to serve as manpower.

Responsible for Reich deployment

Responsible for Reich deployment

Verantwortliche für den „Reichseinsatz“

Many persons on many levels participated in the forced labour system. In addition to the political leadership in Berlin and the occupied areas, countless businesses, government agencies, offices, and organizations were involved.

Albert Speer

Albert Speer (1905–1981) joined the National Socialist German Workers’ Party NSDAP in 1931 and began working for the Nazi government in 1933.

In 1942 Speer was appointed “Reich Minister of Armament and Munitions”. Although aerial attacks destroyed many factories and transport routes, armaments production was ramped up continually until 1944. This was only possible through the exploitation of forced labourers and concentration camp inmates. Speer cooperated closely with the SS and the Gestapo. In 1942 he was involved in drawing up the resolution to set up subcamps on factory premises.

On 1 October 1946, the International Military Tribunal sentenced Speer to 20 years imprisonment. He was released on 30 September 1966.

Albert Speer (right) and August Eigruber, the Gau leader of the Upper Danube region, with concentration camp inmates in the Mauthausen concentration camp, June 1944

Mauthausen Memorial, photo archive P/13/14/1, photographer: Hanns Hubmann

Fritz Sauckel

Fritz Sauckel (1894–1946), a member of the Nazi party from 1923 onwards, held the rank of Obergruppenführer of the SA and the SS. In 1932 he became a minister and the Reich governor of Thuringia.

In 1942 Sauckel was appointed “General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment”. Under his authority, workers were procured from all over Europe for the German Reich. This process was achieved with increasingly overt violence. Wehrmacht soldiers and police deported hundreds of thousands of persons to the German Reich from Eastern Europe.

On 1 October 1946, the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg sentenced Sauckel to death by hanging. The execution was carried out on 16 October.

Fritz Sauckel on a visit to Kiev, June 1942

Yad Vashem, no. 132EO8

Employment office

Employment office

Arbeitsamt

The employment office played a key role in the distribution and placement of workers in Frankfurt. For employers wishing to engage foreign civilian workers or prisoners of war, the first step was to apply to the employment office.

After examining the application, the employment office assigned the applicant foreign civilian workers or—in coordination with the responsible POW camp – prisoners of war. In the POW camp, the employment office had a branch office which assembled the work crews hired out to the applicants.

The employment office had the authority to impose compulsory service. This prevented the foreign civilian workers from being able to return to their homelands at the end of their employment contract. Persons who had originally come to Germany voluntarily thus became forced labourers.

Social security

Social security

Sozialversicherungen

Foreign civilian workers were also required to make social security contributions (including unemployment insurance) from their wages. However, they did not receive social security benefits. This was especially true of civilian workers from Poland and the Soviet Union. In hospitals they were treated as second- and third-class patients. If they had health problems, they could be transferred to other camps with poor medical care or sent home.

Many were murdered in state sanatoria and Nazi killing facilities.

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht (the German army) was responsible for the prisoners of war. It kept them under guard and established and operated the POW camps. The Wehrmacht employed many civilian forced labourers as well.

The Bad Orb POW camp

The Bad Orb POW camp

Stalag Bad Orb

After the beginning of World War II, the Stalag IX B camp was established at the crossroad in Bad Orb. It consisted of 20 wooden barracks for prisoners of war assigned to labour duty. Along with Stalags IX A Ziegenhain (Schwalmstadt/Eder-Trutzhain) and IX C (Meiningen) it was one of three POW camps in the Kassel military district. Prisoners of war were sent from the camp to various locations to work.

The Bad Orb POW camp

Stalag Bad Orb

Aerial photograph, 1945

Repro: Archiv Zeigler

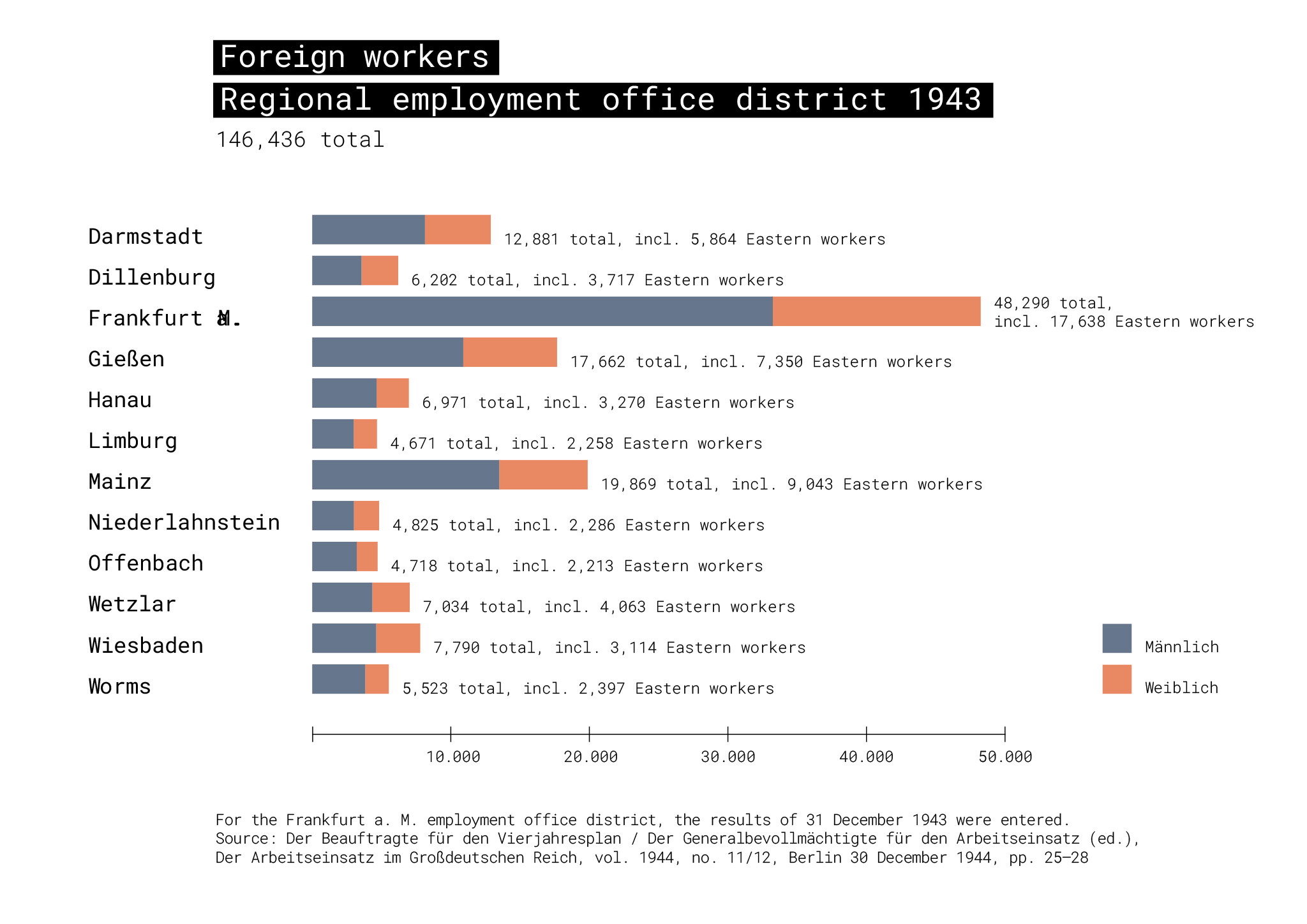

The regional employment office

The regional employment office

Gauarbeitsamt

In the summer of 1943, the 26 state employment offices were converted into altogether 40 “Gau” (regional) employment offices. The Rhine-Main regional employment office based in Frankfurt’s Sachsenhausen district oversaw 12 branches, including those in Darmstadt, Giessen, Mainz, Hanau, Offenbach, and Wetzlar. It coordinated the assignment of foreign civilian workers in the region. It also ran a “transit camp” in Kelsterbach, and – along with the Kurhessen regional employment office – a “sick camp” in Pfaffenwald near Hersfeld.

This authority sent Eastern workers afflicted with tuberculosis or classified as mentally ill to Hadamar. About 700 forced labourers in all were murdered in Hadamar.

The Kelsterbach transit camp

The Rhine-Main state – and later regional – employment office operated a transit camp for forced labourers in Kelsterbach. The camp was surrounded by a fence and guarded. Its 25 barracks provided space for 2,000 persons. From here the camp inmates – presumably several tens of thousands over the course of the camp’s existence – were sent out to their workplaces.

Sick Eastern workers were taken from the Kelsterbach camp to the Hadamar Nazi killing facility or the state sanatorium in Eichberg. There was also an auxiliary hospital where abortions were carried out on female Eastern workers living in Frankfurt and environs – in part against their will.

Kelsterbach transit camp

Frankfurter Volksblatt of 10 May 1942

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main, S6b/93 A

Pfaffenwald camp

The Pfaffenwald transit camp near Bad Hersfeld served the purpose of distributing forced workers in Northern Hesse. It was run by the regional employment office of Kurhessen, which, along with the Rhine-Main regional employment office, also used it as a camp for the sick. Polish and Soviet labourers no longer fit for work were sent there. Many of them died in Pfaffenwald or were transferred to the Nazi killing facility in Hadamar.

Foreign workers

Gestapo

The Gestapo (Secret State Police) were responsible for the surveillance and punishment of all civilian forced labourers and the Soviet prisoners of war. Whereas the SS oversaw the concentration camps, the “work education” camps were managed by the Gestapo. During World War II, these punitive camps were intended primarily for foreign civilian workers. Grounds for committal included laziness at the workplace, refusal to work, leaving the workplace, escape, or violating the prohibition on contact. The Gestapo also kept watch over the private households employing foreign civilian workers as domestic aids.

The Heddernheim “work education” camp

A so-called work education camp (“Arbeitserziehungslager”; AEL) went into operation in the Heddernheim district of Frankfurt on 1 April 1942. It consisted of three barracks, several sheds, and a guard room in the clay pit of a brick factory. There was also a detention cell building, called a “bunker”, for penalization. Although the camp was designed for 200 persons, there were more than 400 detained there at times—Germans as well as foreign civilian workers. Altogether 10,000 persons were held here over the course of the camp’s existence.

The camp regulations spelled out the purpose of the AEL in unequivocal terms: “Prisoners must be made to work hard in order to impress upon them their behaviour that is harmful to the [German] people, to train them to perform well-regulated work, and to set a deterrent and warning example to others.”

The inmates were hired out to various companies as well as the City of Frankfurt as manpower. “Eastern workers” were regularly subjected to shackling and flogging. The sources also document several shooting executions for “looting” and “refusal to work”.

The tax authority

The tax authority

Finanzamt

Not only the employers profited from the forced labour system. It was also financially beneficial to the state. The employers were required to pay income tax to the revenue office. For Polish civilian workers they were charged an additional 15 per cent “social compensation tax”. Eastern workers had to pay an even higher “Eastern worker tax”.

DAF – German Labour Front

DAF – German Labour Front

Deutsche Arbeitsfront

The “Reichsnährstand” (“Reich Food Society”) was responsible for the “care” of the foreign workers assigned to work in agriculture. For all other areas of the economy, the “Deutsche Arbeitsfront” (DAF; “German Labour Front”) fulfilled this function. After labour unions were banned, the DAF Hessen-Nassau took over the Frankfurt union building. There the central labour deployment office coordinated the management of the camps for foreign civilian workers in Frankfurt am Main. It oversaw the camps and was in charge of “leisure time activities” in them.

Municipal administration

Municipal administration

Städtische Verwaltung

The municipal administration was involved in the forced labour system in a variety of ways. It benefited by exploiting the manpower of prisoners of war and foreign civilian workers for its own purposes. A range of administration offices were involved in many of the system’s mechanisms – for example the establishment of camps (building department, trade supervisory board) and the provision of rations (nutrition department). The municipal health department, the board of education, and the cemeteries department likewise helped organize various aspects of forced labour.

Local police

Local police

Ortspolizei

All residents of Frankfurt were registered with the local police – including the forced labourers. The police kept watch over the forced labourers in the urban space, made arrests, and turned the arrested persons over to the Gestapo. They also oversaw the camps located on private company premises, in some cases at the behest of the health department.