Historical Site

Factory, Forced Labour, Concentration Camp

The Adlerwerke contributed to shaping life and work in the Gallus district for some 120 years. Adler products were well-known and sought-after the world over.

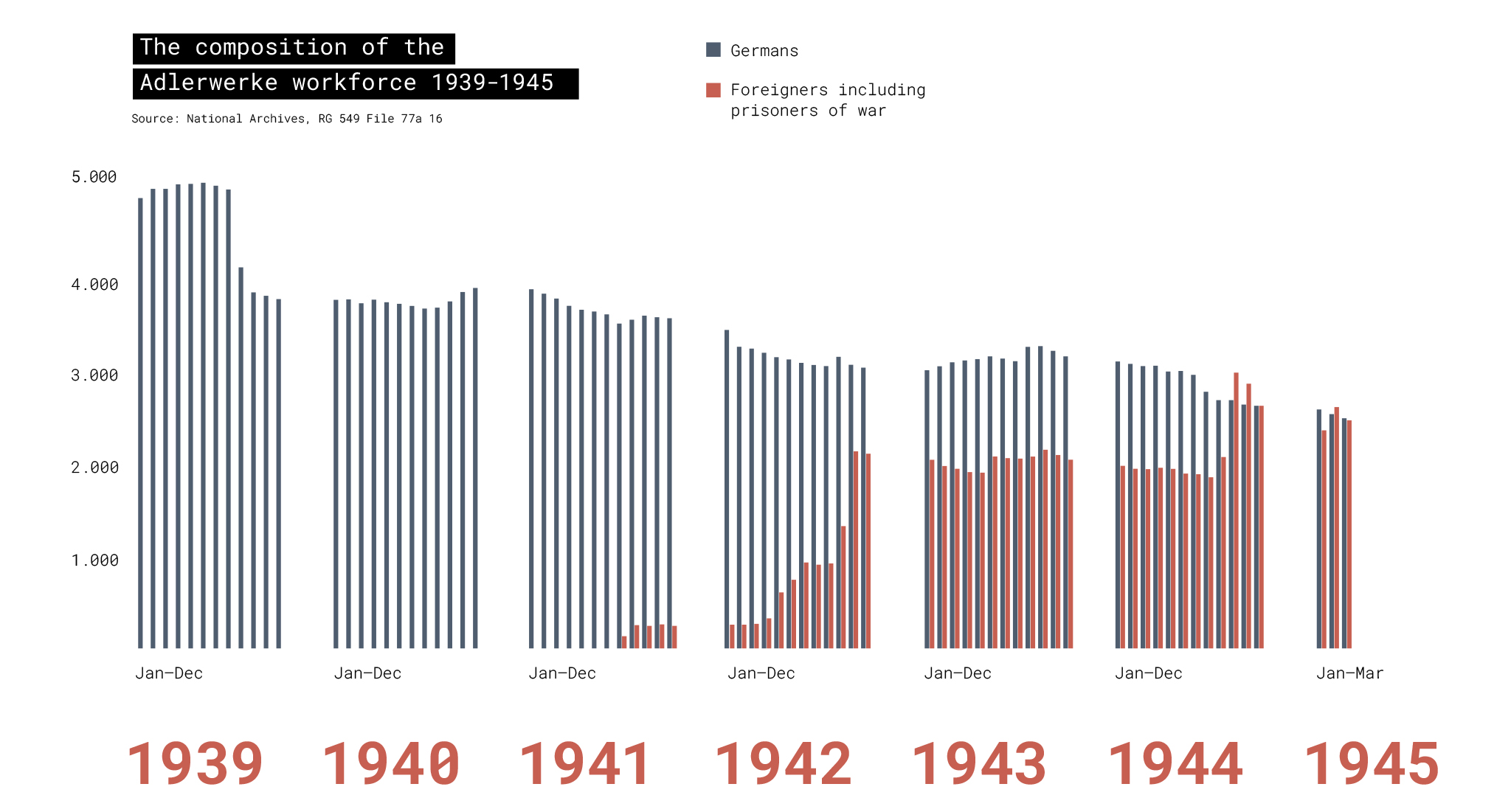

During World War II the company manufactured armaments – and, like many other large-scale industrial operations, profited from the forced labour system. But the foreign civilian workers and prisoners of war in Frankfurt am Main, presumably numbering more than 50,000, were also put to work in trades businesses, farming, private households, and the municipal administration.

The Katzbach concentration camp was set up in the Adlerwerke factory buildings in August 1944. Now the company was part of the National Socialist concentration camp system. Altogether 1,616 inmates would be imprisoned in the camp. Many of them did not survive it.

The Adlerwerke Historical Site is the result of a struggle by citizens to preserve the place and its history. It is dedicated to the victims of the Katzbach concentration camp and forced labour.

Timeline

Adlerwerke and Gallus from 1880

Adlerwerke und Gallus seit 1880

1880 Heinrich Kleyer (1853–1932) opens a machine and bicycle shop. The company produces Germany’s first low-wheel bicycle. The pneumatic tyre is also a novelty. From 1887 onwards, Heinrich Kleyer supplies the Prussian ministry of war.

Heinrich Kleyer, ca. 1930

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main,

inv. W1-14 no. 1077, photo: Voigt

1898 The company later known as the Adlerwerke is built in the Gallus district between the present-day Kleyer and Weilburger streets. Ever more industrial operations are established in Gallus. Migrant workers settle near the factory.

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main,

S7A no. 1998 – 28933

1898 The Heinrich Kleyer AG is the first German company to manufacture typewriters in series. Their design is based on an American patent.

1900 The Adler Model 7 typewriter goes on sale. It will be a national and international bestseller. The company introduces its first motorized vehicle, likewise called Adler, and the following year the first two-wheel motorcycle. The company name is now “Adlerwerke”.

Historisches Museum Frankfurt,

inv. S1971.038, photo: U. Dettmar

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main,

S7A no. 1998–28940

1901–1904 The Hellerhof “workers’ colony” is built.

Advertising postcard, after 1904 (detail)

Geschichtswerkstatt Gallus / D. Church Collection

1905 The “Konsumverein für Frankfurt und Umgebung” (Consumer Association for Frankfurt and Environs) is founded in Gallus. It guarantees its members basic goods at low cost.

Konsum shop at Lahnstrasse 5, ca. 1908

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main,

S7A no. 1998–12156

1910 The production of accounting machines gets underway. The first Klein-Adler typewriter goes on sale in 1913. The Adlerwerke workforce numbers some 7,000.

1914–1918 The Adlerwerke presents itself as a company loyal to the nation and the emperor. It is proud of its involvement in World War I. It produces military lorries, tank transmissions, aircraft engines, torpedoes, grenades, and water bombs.

Archiv Axel Oskar Mathieu, Berlin 1916

1916 The 500,000th bicycle is produced. One in five automobiles in Germany is an “Adler”.

1923 In October, Adlerwerke workers protest the planned shutdown. A general strike with demonstrations on Römerberg Square is quickly dispersed.

1926 Automobile production is converted to the assembly line system. Fewer workers are needed. Since 1920, typewriter production has been back to full speed. Model 25 goes on sale. This machine modernizes office work. It facilitates the use of the “continuous form”.

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main,

W1-14/755

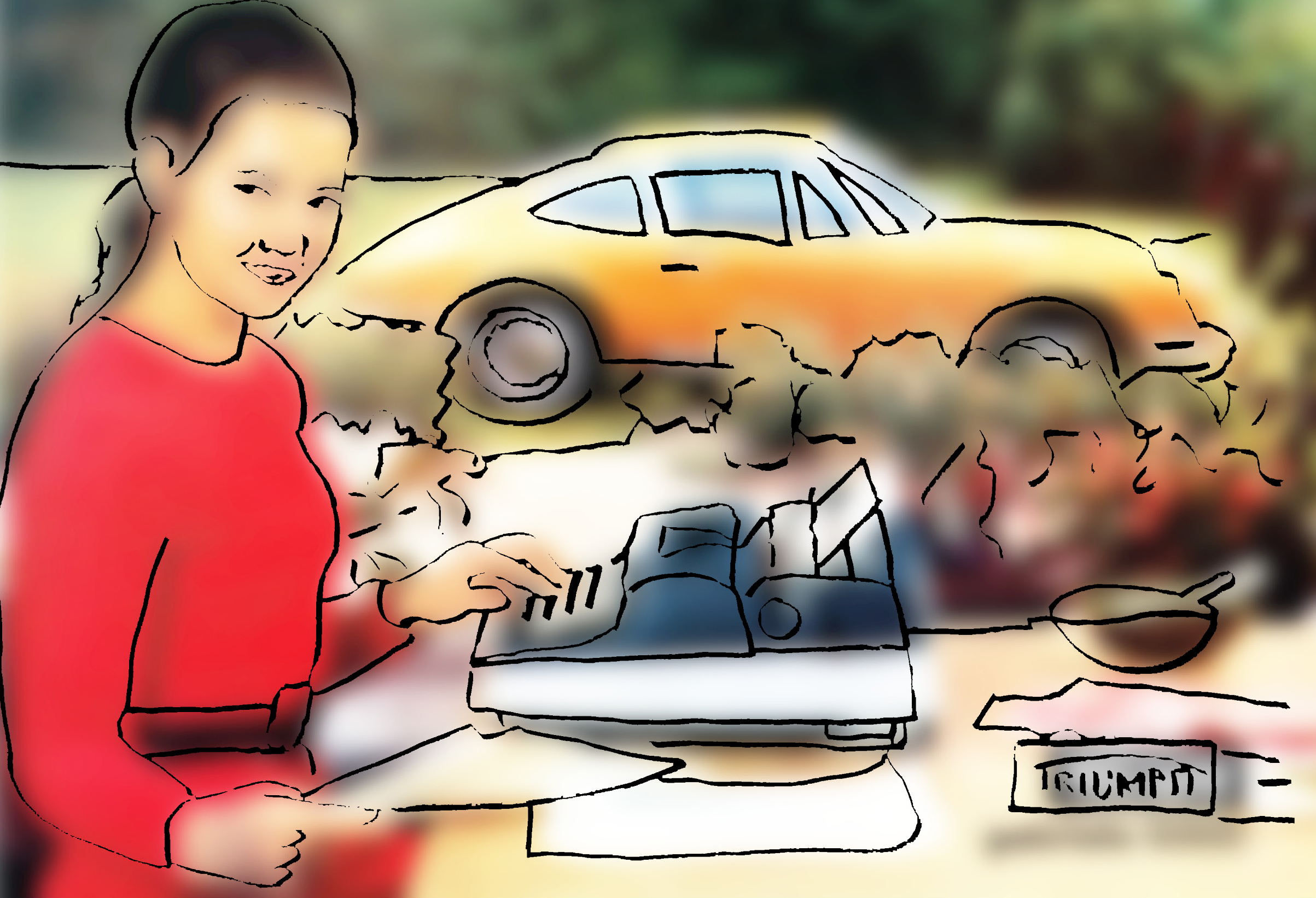

1927 The Klein-Adler Model 2 travel typewriter is a bestseller. It is light and requires less manual strength to operate.

TA Triumph-Adler GmbH

1929 The Great Depression causes the Adlerwerke difficulties. The company workforce declines from 10,000 in the early 1920s to approximately 3,800 in 1931. There are labour struggles involving strikes, lockouts, and dismissals.

1929–1936 The new Hellerhof housing estate is built.

Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt am Main,

S7A 1998–12228

1930 Walter Gropius, the director of the Dessau Bauhaus, designs car bodies for Adler as well as the eagle emblem with spread wings. (“Adler” is the German word for “eagle”.)

1933 On 2 May, two Social Democratic members of the Adlerwerke works council are arrested in the factory. They are detained for six weeks in the “Perlenfabrik”, a temporary concentration camp in Ginnheim.

1936–1938 With support from the Nazi party NSDAP and the Dresdner Bank, the Adlerwerke acquires four companies formerly owned by Jews, among them the Carl Flesch AG. This enables the Adlerwerke to expand its manufacturing facilities.

Geschichtswerkstatt Gallus

1937 The Nazi government subsidizes the automobile industry. By 1939, 6,000 of the state-of-the-art “Adler Typ 10” have been built.

Reich Chancellor Hitler with an “Adler Typ 10”

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main,

S7A no. 1998–29020

1939 The Adlerwerke converts its operations to armaments production.

Archiv Axel Oskar Mathieu, Berlin

1941 Prisoners of war and foreign civilian workers work for the Adlerwerke.

1943 The Adlerwerke is Europe’s largest manufacturer of armoured personnel carrier chassis.

1944 In August the company sets up the Katzbach concentration subcamp in its factory. The camp will lodge more than 1,600 inmates.

1945 On 24 March, the last Katzbach concentration camp inmates are forced to depart on a death march. When the war ends, a large proportion of the factory facilities is in ruins. The Gallus district has suffered extensive destruction through aerial attacks.

Geschichtswerkstatt Gallus/Hergt

1949 After 1945, the Adlerwerke stops manufacturing automobiles. Now it resumes production of bicycles, typewriters, and spare parts for cars, which it also repairs.

1954 Bicycle production ceases.

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main,

S7C no. 1998–63818

1955 The Adlerwerke produces more than 100,000 typewriters. They lead the market in Germany and the world.

1957 Motorcycle production ceases. The company merges with the Triumph-Werke of Nuremberg and manufactures typewriters and office machines. The company will change hands several times over the next thirty years. In addition to the factory in Gallus, it operates one in Griesheim.

1960s Increasing numbers of “guest workers” from other European countries live in Gallus. The German economy needs workers.

Workers leaving the factory, 1963

Bpk, no. 70366483, photo: Abisag Tüllmann

1969 Triumph-Adler produces Germany’s first portable electric typewriter: the “Gabriele 5000”.

TA Triumph-Adler GmbH

1971 Computer-supported office work gets underway successfully with the TA 10 “people’s computer”.

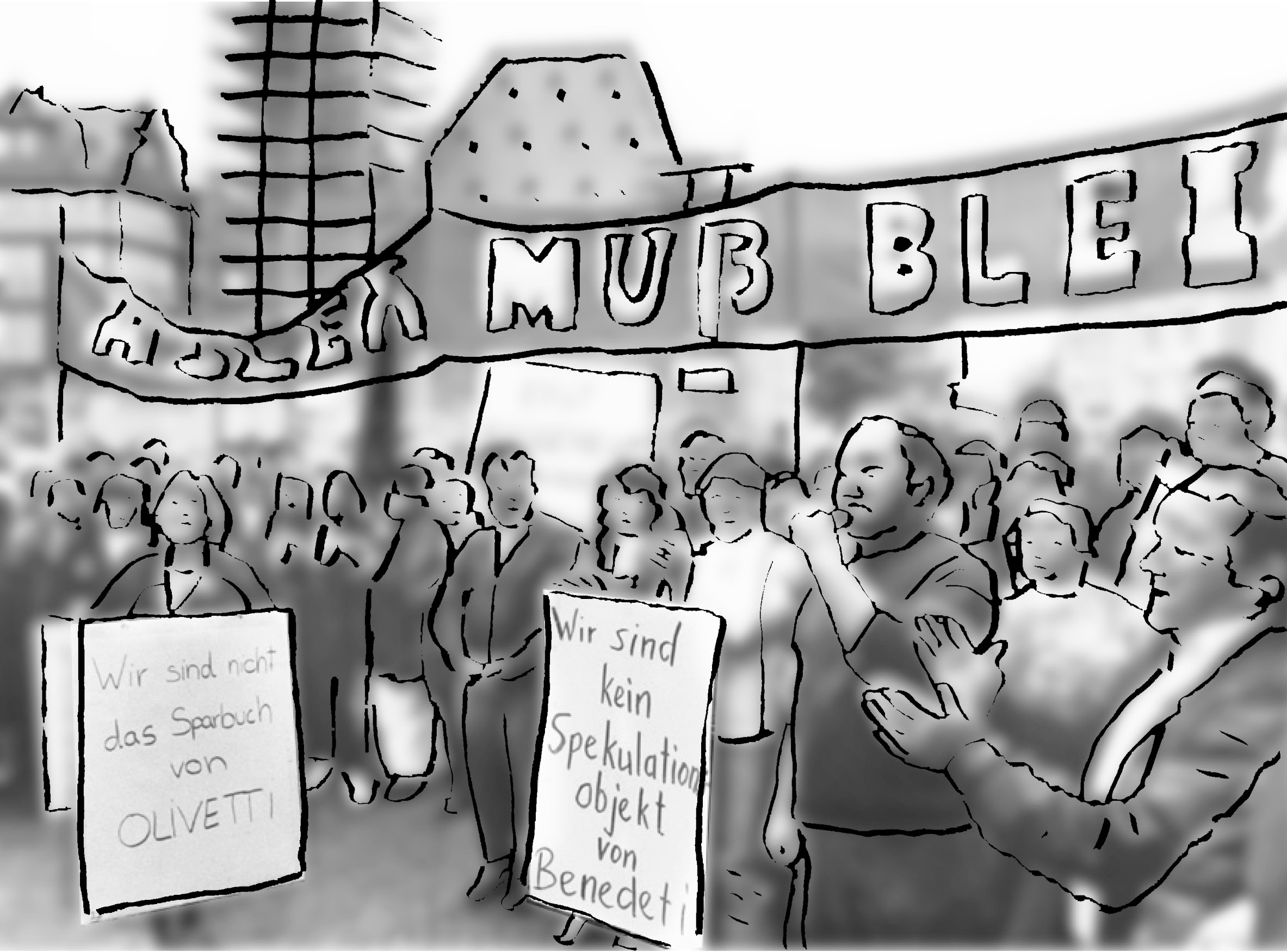

1980 The workforce resists the management’s plan to close the plant.

Demonstration against the Adlerwerke shutdown, 1980

Photo: W. Ullrich, Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main,

S7FR 1226

1988 The first scholarly study on the Katzbach concentration camp develops out of a school project. The book by Ernst Kaiser and Michael Knorn comes out in 1994.

1992 The plant in Gallus is closed. Typewriter production continues in Frankfurt’s Griesheim district. The workforce resists the shutdown.

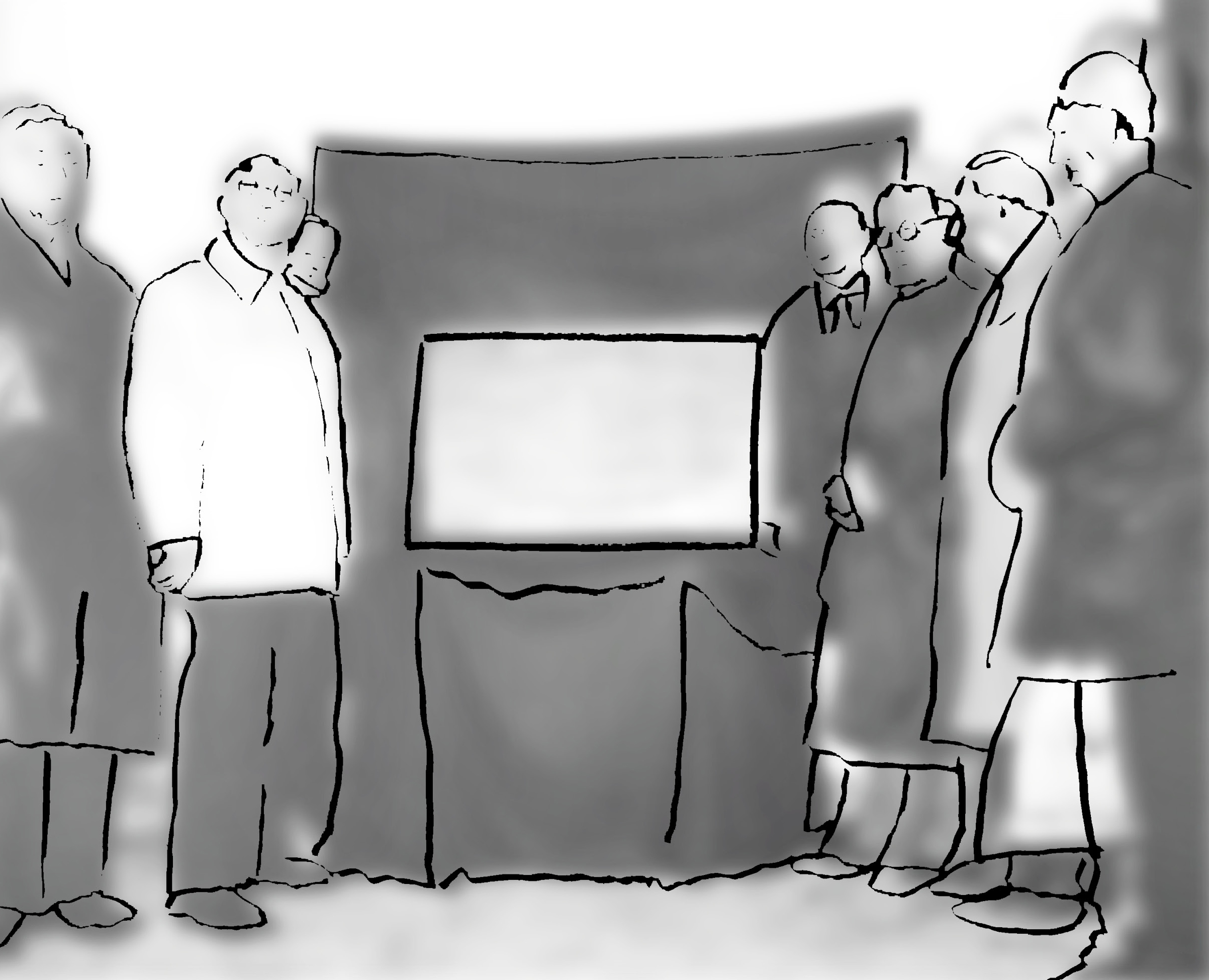

1993 The historical factory grounds in Kleyerstrasse are sold to the real estate investor Roland Ernst and the Philipp Holzmann construction company. On the initiative of the Adler works council, a plaque is installed at the Adlerwerke to commemorate the victims of the concentration camp and of forced labour.

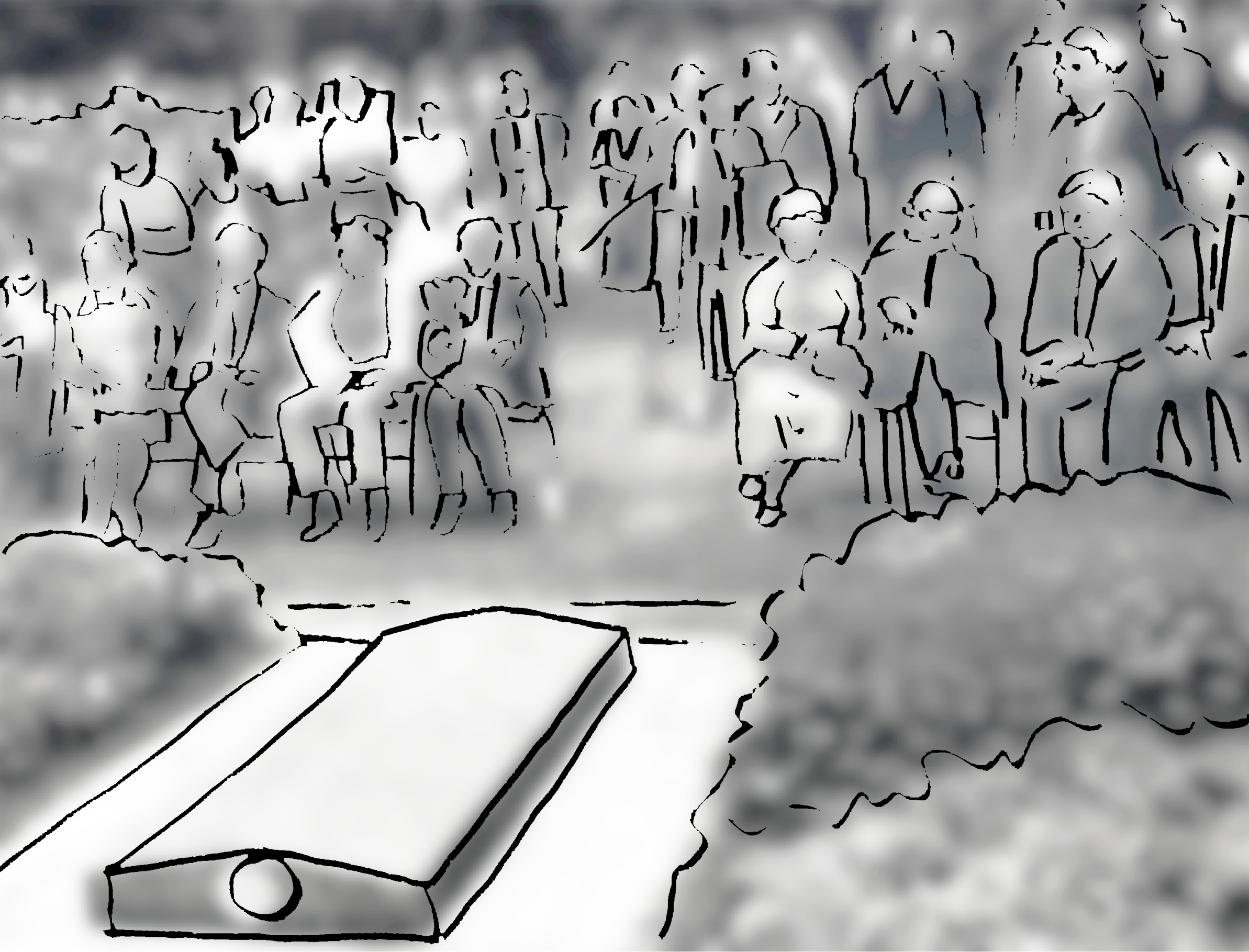

The commemorative plaque is unveiled

at the Adlerwerke with former concentration camp inmates.

Source: LAGG e.V.

1997 Dedication of a commemorative stone at the main cemetery for the victims of the Katzbach concentration camp.

Katzbach concentration camp survivors

at the memorial service, 1997.

Source: LAGG e.V.

1998 Production in Frankfurt is discontinued. The Gallus-Theater moves in. Former forced labourers and inmates of the Katzbach concentration camp visit Frankfurt. On the initiative of individual citizens and associations, a square is named after the concentration camp inmates Golub and Lebedenko, who were murdered by the SS.

Photo: Svenja Cloos

1999 The Adler Real Estate AG company takes over the company building.

2012 Since 2012, several art actions in Frankfurt and along the route of the death march commemorate the victims of the Katzbach concentration camp.

“Mitten unter uns” (“In our midst”)

Art installation, 2015

Photo: Stefanie Grohs

2016 On the initiative of citizens’ groups and individual citizens, a public park is newly landscaped and named after Julius Munk.

2022 The Adlerwerke Historical Site opens.

Theme box: Ernst Hagemeier (1888–1966) Company manager during the Nazi period

Ernst Hagemeier (1888–1966) Company manager during the Nazi period

Ernst Hagemeier (1888–1966) Betriebsführer im Nationalsozialismus

Between boycott and “Aryanization”

Ernst Hagemeier became a member of the Adlerwerke’s executive board in 1929. As general director he soon rose to become the company’s main shareholder.

The Adlerwerke did not support the National Socialist party (NSDAP) financially before 1933. In that year, the Nazis therefore called for a boycott of the Adlerwerke. Following the party’s accession to power, Hagemeier saw to it that not all Jewish employees were dismissed. He sent many of them to work in subsidiaries abroad. The Nazis accordingly accused him of “friendliness to Jews”.

On the other hand, when Jakob Goldschmidt came under threat of being chased off the supervisory board, Hagemeier did nothing to prevent it. Under his management, the Adlerwerke profited from “Aryanization”. It was able to purchase, at low prices, the land of four neighbouring companies whose owners were persecuted as Jews. The Adlerwerke thus expanded its property.

Member of the Nazi party and the SS

In 1933, Ernst Hagemeier applied for membership in the Nazi party NSDAP. He was not admitted until 1939. He moreover joined the General SS, where he had the rank of an SS Untersturmführer.

He worked for the SS as an expert on automobility. In 1934/35 he became the head of the “Motorized Vehicle Industry Economic Group”. There he came into conflict with influential National Socialists who wanted to promote party interests. As a result, he gave up the post again in 1937.

In 1937, the Munich SS court excluded him from the organization. The grounds for this decision were that he had not attended SS events and continued to cultivate business contacts with Jews.

Responsibility for armament, forced labour, and concentration camp

General director Hagemeier was a pragmatic manager. He made sure his dealings with the Nazi regime would work to the company’s advantage. Starting in 1939, the Adlerwerke increasingly took on armaments’ orders and Hagemeier received the honorary title “Wehrwirtschaftsführer” awarded to the heads of important armaments manufacturers.

Ever more company employees were conscripted to the Wehrmacht, and the Adlerwerke needed replacements. Now foreign civilian workers and prisoners of war from France and Eastern Europe were brought in. These workers lived in camps in the Gallus and Griesheim districts. Concentration camp inmates were put to work at the Adlerwerke from August 1944 onwards. The “Katzbach” concentration camp was set up on the factory premises.

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main,

inv. S2, no. 2216

Theme box: Gallus – A changing community

Gallus – A changing community

Das Gallus – Ein Stadtteil im Wandel

The name “Gallus” has its origins in the gallows once set up outside the city gates in the west of Frankfurt. The district evolved from 1884 onwards along the newly constructed railway line. Factories were established outside the town limits and needed manpower. The latter came from the surrounding regions. Housing, schools, churches, shops, and inns sprouted up to serve them. Since 1895, a tram line has connected the Gallus district with the city centre. The City of Frankfurt had the Hellerhof housing estate built between 1901 and 1936. It provided affordable housing for low-income persons.

Many of the Gallus district’s residential buildings and industrial operations were destroyed during World War II. After that, fewer people lived in the district than before. The factories gradually converted their production or shut down altogether. Service companies, administrative offices, and the media moved into the old buildings or constructed new ones. The residents’ occupational skills no longer corresponded to the available jobs. Unemployment and crime increased.

Around the year 2000, Gallus ranked as a deprived area. The city subsidized the district between 2001 and 2016. Municipal administration offices moved there. The transformation of the Gallus district continued. A new quarter—the “Europaviertel”—was built on the grounds of the former freight yard. It is an expensive residential area. New residents shape the community, but they work in offices and not in industrial production like the inhabitants of Gallus a hundred years ago.

Kamerun

“Kamerun” (German for Cameroon) – Isn’t that a country in Africa? But people have been calling the Gallus “Kamerun” for more than a hundred years. There are two explanations, both of which are indirectly racist in nature.

Explanation 1: After World War I, France occupied western Germany. Black French soldiers were stationed near Frankfurt—an unusual experience for white Germans.

Explanation 2: Smoke from the factory smokestacks and the railway coloured people’s clothing black and the workers came home from the factories with faces blackened by oil and soot. It was a racist notion to equate them with people from Africa.

What is more, these explanations cannot possibly be correct. There are spoken and written references to the “Kamerun” district dating all the way back to 1902. At that time, there were no bleach greens where smoke could have dirtied the laundry. Nor was there any heavy industry in Gallus, but above all mechanical and electrical engineering companies like the Adlerwerke. The workers washed in a washroom before leaving the factory after work. There were no Black soldiers stationed in the district. Germany had colonies in Africa, but Gallus had no Blacks.

In the early twentieth century, Gallus was planned as a “settlement outside the city to the southwest”. Newly emerging districts outside the city centers often referred to as “colonies”. In general, this was a term used for places outside the familiar sphere. At the time, Germany ruled over and exploited Cameroon as a colony. The name is accordingly reminiscent of German colonialism.

Migration

The Gallus district evolved as a result of migration. The first inhabitants came from villages in the regions around Frankfurt. They were looking for work in the factories and companies that sprouted up in Gallus in the early nineteenth century.

During World War II the Nazi government brought prisoners of war and foreign civilian workers to Frankfurt. Several of the camps used to house them were in Gallus. And it was there that the Katzbach concentration camp was set up in the Adlerwerke.

Starting in the 1960s, “guest workers” came to the district from Southern Europe and Turkey. They had been recruited to serve as manpower; the intention was that they would soon return to their home countries. However, many of them became Frankfurters. They worked alongside Germans in the factories. It would be years before they were able to bring their families to Frankfurt as well. The immigrants founded associations and religious communities.

After 1989, so-called “late resettlers” – ethnic German repatriates – from Eastern Europe followed. People from Africa, Asia, and Latin America often came to the district as refugees. The population of Gallus now represents approximately 140 different nationalities.

The Galluswarte, 2022

Photo: Thomas Altmeyer