> Adlerwerke Historical Site (Foyer)

> A crime that became a part of everyday life

> Zwangsarbeit – ein Verbrechen mitten im Alltag

> The forced labour system

> System Zwangsarbeit

> The concentration camp in the factory

> Das Konzentrationslager in der Fabrik

> Clearance and death march

> Räumung und Todesmarsch

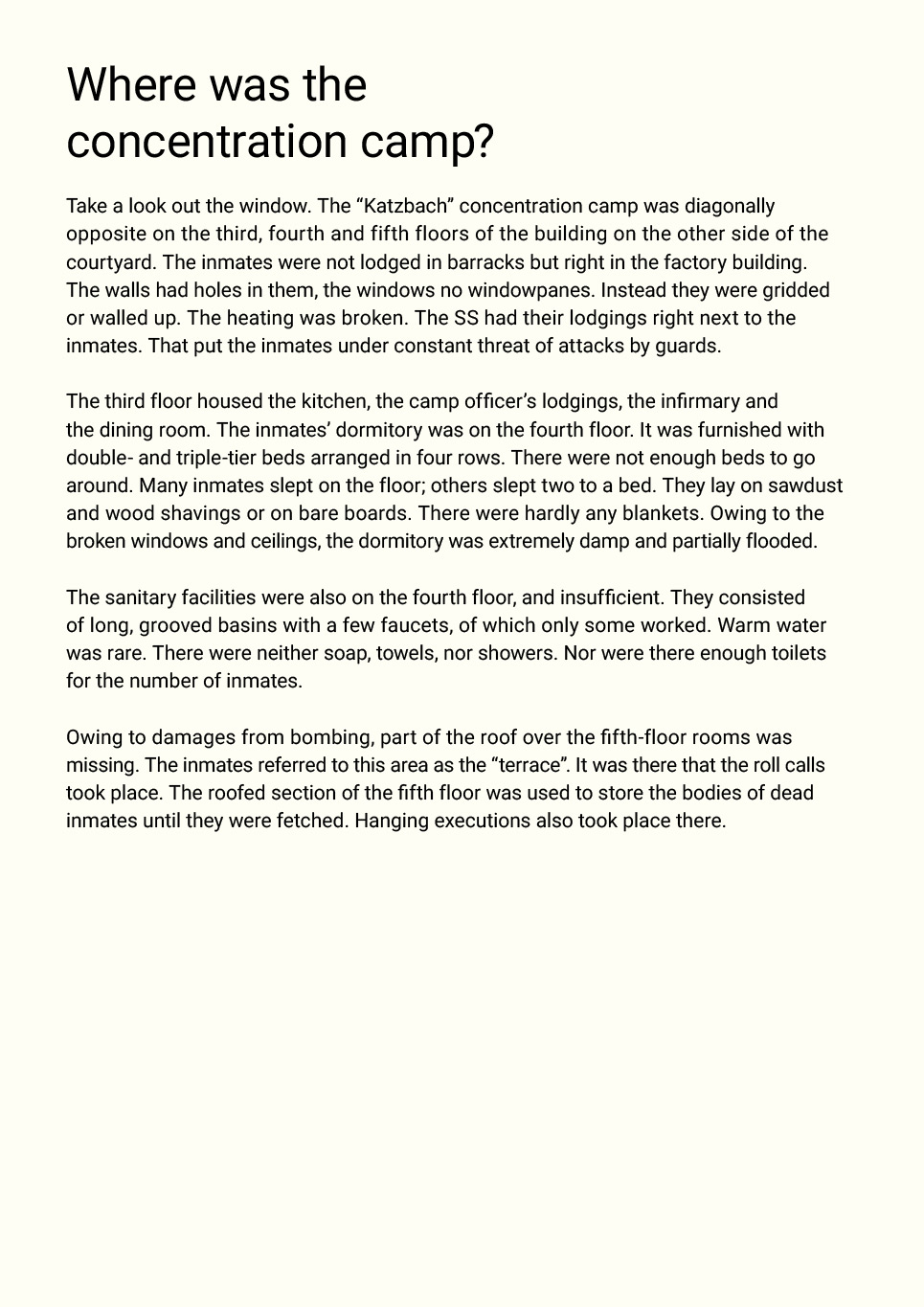

> Conflicts over labour, remembrance, compensation

> Konflikte um Arbeit, Erinnerung, Entschädigung

Conflicts over labour,

remembrance, compensation

Despite the criminal prosecution and denazification activities, the Katzbach concentration camp sank into oblivion. The memory of the forced labourers was repressed. Forty years later, grass roots initiatives broke the silence.

When the Adlerwerke was threatened with closure after 1990, there was resistance from the workforce. It was around the same time that the factory’s history during the Nazi period was brought to light. The survivors’ struggle for compensation dragged on for decades.

Remembrance

Remembrance

Erinnerung

After 1945, the memory of the “Katzbach” concentration camp or the forced labourers was not an issue at the Adlerwerke. When the company celebrated the 90th anniversary of its founding in 1970, there was only brief mention of the Nazi period, and only because the factory had been partially destroyed by bombing in 1944. Things only began to change in the 1980s. It was Adlerwerke employees and the local advisory council 1 that took the initiative.

Active citizens saw to making the crimes and the company management’s responsibility known to the public. It would be 2022 before the commemorative and educational centre was founded.

“There will be nothing left at all! A void will fill this gap. Of that I am convinced. I know there are initiatives to this end, but I don’t really believe the documentation will ever be successfully carried out or a memorial will be erected at the Adlerwerke.”

Wladyslaw Jarocki, “Katzbach” concentration camp survivor

in: Joanna Skibinska, Die letzten Zeugen: Gespräche mit Überlebenden des KZ-Außenlagers “Katzbach” in den Adlerwerken Frankfurt am Main , p. 95

Silence and cover-up—exposure and pressure

In 1986, the Adler employee Lothar Reininger asked some of his older colleagues what they knew about the concentration camp in the factory. They warned him that this question could cost him his job. It took a long, slow process to overcome the silence. The municipal advisory council 1 proposed the installation of a commemorative plaque. At the Paul Hindemith School, Ernst Kaiser and Michael Knorn carried out a history project on the Nazi period in the Gallus district with their pupils. That project marked the beginning of the research. The seminal book about the “Katzbach” concentration camp was one result. Camp survivors were contacted and relationships evolved.

The LAGG association, the Gallus-Theater, and the Claudy foundation joined with various other groups, churches, and individual residents of Gallus to form the “Initiative Gegen das Vergessen” (IgdV; “Initiative against Oblivion”). Over a period of many years, they pressured the decision-makers to erect a memorial for the “Katzbach” concentration camp. They put up a new tombstone on the grave of the concentration camp inmates in the city’s main cemetery. They invited survivors to Frankfurt. The IgdV organized initial compensation payments.

In 2015, a support association took over the task of uniting the players on many levels. Along with other supporters it ultimately succeeded in establishing the Adlerwerke Historical Site.

Taking action

It was in the autumn of 1993 that the LAGG association first laid a wreath on the memorial stone in the city’ main cemetery. Nearly every year since 1995 it has called for a memorial procession on 24 March. That is the date on which the death march departed for Buchenwald in 1945.

Events regularly take place at the Gallus-Theater. Actions along the route of the death march convey its spatial dimensions to the public.

Since 2013, the Office of the Mayor in Charge of Culture and Science of the City of Frankfurt has organized three artistic actions revolving around the concentration camp once existing in the Gallus district.

Visits from forced labourers and former concentration camp inmates

The Triumph-Adler works council and the authors Kaiser and Knorn joined in an effort to get the City of Frankfurt to invite survivors to visit. Ultimately it was the committee “Ausgegrenzte Opfer” (“Ostracized Victims”) that organized and financed the visit. In December 1993, nine survivors came to Frankfurt from Poland.

The visits were extremely moving for the old men from Poland and their hosts. Friendships evolved. The programmes also included discussions in schools and public events. There were several visits from survivors over the years that followed.

“When I look back over my life today, I find that the injuries to my soul have never healed completely, despite all my efforts to attain normality.”

Zygmunt Świstak, “Katzbach” concentration camp survivor

in: Joanna Skibinska, Die letzten Zeugen: Gespräche mit Überlebenden des KZ-Außenlagers “Katzbach” in den Adlerwerken Frankfurt am Main , p. 161

Visits from survivors, 1997

Front row l. to r.: Else Gromball, Kajetan Kosiński, Gisela Hand, Anna Szczyplewska-Görtz, Beata Kumarow, Frau Madej, Stanisław Madej, Jan Kozłowski, J.H. Kilka, Lothar Reininger, Ulla Diekmann – back row l. to r.: Andrzej Cieslinski (son of Jan Cieslinski), Rolf Heinemann, Dieter Bahndorf, Heinz Meyer, Andrzej Branecki, Ryszard Olek, Friedrich Radenbach, Henning Kühn

LAGG e.V.; photo: Karlo Müller

Sites of remembrance

Remembrance of crimes needs visible signs. For nearly 50 years, there was nothing to remember the “Katzbach” concentration camp or the murdered inmates by. It was not until the mid-1980s that the public began to learn about the sites of the crimes. Various actions have called attention to them. Citizens’ initiatives have been responsible for erecting commemorative markers and sites.

Recognition and compensation

Recognition and compensation

Anerkennung und Entschädigung

From around 1990 onwards, initiatives asked ever louder questions about industry’s responsibility for the crimes committed during the Nazi period. Demands were made for compensation for the forced labour performed. German companies were sued in the U.S. Public pressure grew so strong that institutions and companies slowly began to seek compromises. Finally, in the year 2000, the German parliament passed a resolution to establish the foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future”. This organization collects money from private German enterprises to enable payments to survivors. Many former forced labourers began to receive a bit of compensation. Nevertheless the companies never took direct responsibility for their involvement in the crimes.

Recognition

Invitations and meetings with school classes give the survivors the feeling of being heard in Germany. During their visits to Frankfurt, a number of the “Katzbach” concentration camp survivors took part in demonstrations. Others remained cautious. For all of them, public recognition of the injustice they were subjected to is more important than money.

They distinguish very clearly between the Germans they join in protest with and those responsible for the crimes.

Andrzej Branecki in conversation, Frankfurt 2009

Photo: Maciej Rusinek

Compensation for survivors

The Adlerwerke works council and the LAGG association contacted “Katzbach” concentration camp survivors. Ernst Kaiser and Michael Knorn had found out the addresses during their research. In late 1993, eleven former inmates came to Frankfurt on invitation from the city. It was then that LAGG publicly demanded compensation.

Adlerwerke employees made donations to make symbolic compensation payments possible. A donation from the Philipp Holzmann construction company (co-owner of the Adlerwerke for a brief period) and the Frankfurt Jugendring as well as individuals bolstered the available funds. In 1997, 5,500 deutschmarks were transferred to each survivor. It was a symbolic sum. In 1998, the Dresdner Bank was persuaded to pay 8,000 deutschmarks to each of the eleven surviving former “Katzbach” concentration camp inmates known at the time.

“Emergency aid” for forced labourers

Since about 1980 there have been initiatives for the remembrance of forced labourers in Frankfurt. Between 1941 and 1945, they numbered some 50,000. In the year 2000, the city council assembly adopted a resolution to pay “emergency aid” in the amount of approximately 1,000 euros to each former forced labourer. The research to determine who was eligible took several years. The payments got underway in 2000. Several former forced labourers visited Frankfurt in this context. The last group came from Belarus in 2007.

The owners’ responsibility

In 1993, the Adlerwerke works council and the LAGG association call on Triumph-Adler and the Dresdner Bank to pay eleven surviving concentration camp inmates’ adequate compensation. From 1939 onwards, the chairman of the company’s supervisory board had come from the Dresdner Bank. The latter was also a majority shareholder of the Adlerwerke after 1945.

A demonstration in 1995 ends with the delivery of an open letter to the Dresdner Bank. However, the bank denies bearing any specific responsibility.

In July 1998, the Dresdner Bank pays those of the former Adlerwerke concentration camp’s former inmates still alive at the time a total of 80,000 deutschmarks. The bank representatives insist that the money is not compensation but “humanitarian aid”. They refuse to acknowledge the bank’s share of the blame.

“I would like to emphasize that I did not demand anything there. It was union people who demanded reparation for our slave labour. I would not have mentioned anything of the kind in any of my speeches. I even said: ‘We come here not as supplicants to ask for something …’ Because we didn’t want to. That’s why the LAGG fought that fight.

Rather, I thought about what form of compensation there can even be when you’ve lost your family, your home, your humanity, and been treated like a slave, like scum.”

Wladyslaw Jarocki, “Katzbach” concentration camp survivor

in: Joanna Skibinska, Die letzten Zeugen: Gespräche mit Überlebenden des KZ-Außenlagers “Katzbach” in den Adlerwerken Frankfurt am Main , pp. 92/93

“No, I didn’t go to Frankfurt. I don’t like demonstrations. But afterwards I got 8,000 deutschmarks from the Dresdner Bank … By the way, that amount was subtracted from the compensation.”

Kajetan Kosinski, “Katzbach” concentration camp survivor

in: Joanna Skibinska, Die letzten Zeugen: Gespräche mit Überlebenden des KZ-Außenlagers “Katzbach” in den Adlerwerken Frankfurt am Main , p. 110

Labour

Labour

Arbeit

After 1945, the Adlerwerke manufactured two-wheeled vehicles and office machines. Approximately 3,000 persons worked here. The company changed hands several times. Around 1990, “Triumph Adler” owned the Olivetti office machine company. At that time, there were still some 600 jobs. However, speculation with real estate proved more profitable for the capital owners than production. The factory buildings were sold and the factory closed. Where the “Adler” buildings once spread out over many kilometres in the Gallus working-class district there are now housing estates and office buildings.

The works council and the workforce began protesting the job cuts and the complete shutdown of Triumph-Adler in 1980. Their successes would not last.

From around 1960 onwards, the Gallus district was shaped by the immigration of “guest workers”. The industry needed labourers. It was not long before the district was as diverse as the Adler workforce. But it also long ranked as a social hotspot.

Life and Work in Gallus and Griesheim: The LAGG association

The LAGG association is founded by TA Triumph-Adler company employees in 1992 as a self-help project. It first success is to secure company housing for the tenants in Bingelsweg in the Griesheim district.

Triumph-Adler has sold the flats belonging to the company and the “Adlerwerke” public limited company in a single package. By exerting political pressure, the LAGG enables the purchase of the estate with 42 flats by the tenants and LAGG.

Before shutting down the Adlerwerke, Triumph-Adler cuts social benefits. LAGG takes over the operation of the cafeteria and the factory bus for non-resident employees (among other services) for several years. It also organizes further training for employees and founds an employment association.

Since its inception, LAGG has played a decisive role in the struggle for the reassessment of, compensation for, and remembrance of the atrocities committed in the Adlerwerke’s Katzbach concentration camp.

In-migration

The Gallus district evolved around 1900 as an industrial location where factory and railway workers lived. They had come to Frankfurt from the surrounding regions. The district is characterized by migration to this day. Starting in the 1960s, increasing numbers of workers came from Italy, Spain, Greece, and Turkey. Until into the 1970s, these “guest workers” often lived in collective accommodations. They remained in communities that spoke their native language, hardly entering into contact with other groups. The social welfare office and the churches organized care services. The German government expected the “guest workers” to return to their countries of origin when they were no longer needed on the labour market. Most Germans kept a distance or were actively xenophobic.

In the political struggles for work and housing, the immigrants played an ever greater role. In 1981 there was a “foreigners’ list” in the Adlerwerke works council election. Cultural activities, churches, and childcare became places of encounter. Today the term “foreigner” is no longer appropriate. The Gallus district thrives on the diversity of its residents.

Gallus Centre and Gallus Theatre

Around 1970, the Gallus was shaped primarily by labour in industrial enterprises. Many migrant workers lived here. In 1973, left-wing students and “guest workers” founded the “Internationales Solidaritätszentrum” (International Solidarity Centre). Two years later it went into operation in a workshop space at Krifteler Strasse 55. Above all “foreign” teens and children gathered at this “Galluszentrum”, as it was called for short. In 1978, the “teatro siciliano” developed out of educational work. It was the first “guest worker” theatre group in the then Federal Republic of Germany. The group soon called itself “I Macap” and became internationally successful.

After several years, the “teatro siciliano” disbanded. Some of those active in it became professional actors; others founded shops or restaurants. The Galluszentrum split into two institutions: The Gallus-Theater became an important stage for free theatre groups and the old Galluszentrum devoted itself to media education work with young people.

Protests against the Adlerwerke shutdown

Again and again, protests prevent the factory’s shutdown. In a six-week strike, the workforce once again prevails in 1991. Nevertheless, the factory facilities in the old Adlerwerke are abandoned. Factory operations continue only in Griesheim—with half the workforce. Finally, in 1998 Triumph-Adler ends the production of office machines, in which around 100 employees were still working. The Frankfurt factory is thus closed once and for all.

The labour dispute helps a large proportion of the employees to make the transition to retirement. For many other Adler employees, however, there are few opportunities on the labour market.

The struggle for jobs is closely associated with the exposure of the history of “Katzbach” concentration camp. The works council publicly decries the responsibility of the company management and the Dresdner Bank as the Adlerwerke’s majority shareholder.

Legal proceedings

Prosecution for the crimes committed in the Adlerwerke

Strafverfolgung der Verbrechen in den Adlerwerken

U.S. Army jurists began investigating the crimes committed in the Katzbach concentration camp on 22 July 1945.

The judicial authorities of the Federal Republic of Germany continued inquiries into the actions of the Adlerwerke company management, the SS camp command, and the guard units until the 1990s. The camp had been dissolved in great haste in March 1945. There were accordingly few written documents. That made it difficult for the American and later the German investigators to determine the names of the SS men stationed at the Katzbach camp.

The SS camp command and the Adlerwerke company management went unpunished.

SS camp command

Already the American investigators had identified camp commandant Erich Franz as the person chiefly responsible for the Katzbach concentration camp. Because his whereabouts were unknown, they were unable to charge him with war crimes. The Hessian State Criminal Investigations Office finally tracked Franz down in Vienna in 1963. The case was then turned over to the Austrian authorities. They discontinued the proceedings in February 1967 because several of the key witnesses were no longer alive.

The deputy camp commander SS Oberscharführer Emil Lendzian went underground. Neither the American nor the German investigators were able to locate him. He died in 1956 before the Hessian State Criminal Investigations Office was able to learn his whereabouts.

Not a single member of the Katzbach concentration camp command had to answer for the crimes committed in the camp.

SS guard units

The American investigators’ efforts to find the former SS guards were not crowned with success. Starting in 1959, the Hessian State Criminal Investigations Office pursued proceedings against the guards Otto Rogge, Karl Neumann, Artur Malzkeit, Werner Fischer, Sommer, and Sokolowsky for their crimes in the Katzbach concentration camp and on the death march to Hünfeld. It rarely proved possible to find the suspects. Not a single one of them was sentenced. Martin Weiss was convicted of murder on two counts. He was tracked down in his hometown in Romania in 1959. However, the German judiciary did not request his extradition.

Only the two auxiliary guards Heinrich Kiefer and Karl Faust were charged with mishandling inmates; in 1946 and 1947 courts in Frankfurt sentenced them to prison terms of between seven months and three years.

Survivors

In the early years, former inmates managed to initiate criminal investigation procedures. Italian military internees were the first to report on the Katzbach concentration camp to American investigators. After their liberation, most of the forced labourers and concentration camp inmates had tried to return to their home countries. They were no longer in Frankfurt.

A number of the survivors were able to support the proceedings by giving testimony or filing complaints. The former inmates Johann Kopec and Gottlieb Sturm had remained in the vicinity of Frankfurt. They helped disinter the bodies of the persons murdered on the death march.

Survivors incriminated SS guards, the SS camp command, and individual Adlerwerke foremen with their testimony. They also acknowledged the good deeds and help provided by individual company employees.

Management

Investigators learned about the exploitation of forced labourers at the Adlerwerke from the former Italian military internee Gino Righi. He gave them the names of nine company employees who had been involved in the labour deployment activities. They were arrested by the U.S. Army in late July 1945. Among them were the factory security officer Georg Liptau and the head of the “allegiance” office Ernst Werner Sporkhorst. However, neither of them was classified as a perpetrator and both were released from custody in September 1945. They were heard as witnesses.

The investigations shed light on board chairman Ernst Hagemeier and the former head of personnel and authorized signatory Franz Engelmann’s share of the blame for the forced labourers’ life-threatening situation and the crimes committed at the Katzbach camp. The U.S. Army arrested both men on 3 August 1945. They both disavowed any blame and the charges against them were eventually dismissed. In the subsequent denazification proceedings, Hagemeier was classified as a “Mitläufer” (“follower”). Engelmann was arraigned as a major offender, but the case was ultimately abandoned.

Company employees

After the liberation, survivors of the Katzbach concentration camp reported several Adlerwerke employees to the U.S. Army. Nine employees were arrested in late July 1945, among them the “labour deployment engineer” Viktor Heitlinger. He had negotiated with the SS and selected 1,000 Dachau concentration camp inmates for labour in Frankfurt. However, the American investigators were concentrating on the camp command. Heitlinger and two other company employees were therefore ranked not as perpetrators but as witnesses. Heitlinger was released from custody in September 1945.

In the framework of “denazification”, all Germans were required to appear before a special court known as a “Spruchkammer”. Serious allegations were made against Heitlinger. In May 1947, 24 Adlerwerke employees had signed a declaration. They reported that he had mistreated and beaten foreign workers and prisoners of war. They had also witnessed Heitlinger describing himself as an “aggressive Nazi”.

Yet there were also exonerative statements. The former inmate Gottlieb Sturm testified that Heitlinger had given food to inmates. On 30 April 1949, the manager was classified as a “Mitläufer” (“follower”). The American authorities informed the Polish judiciary about the charges against general director Ernst Hagemeier and other responsible persons in the Adlerwerke. Only the worker Karl Grass was turned over to Poland. He was accused of having mistreated Polish forced labourers. On 21 December 1949 he was committed to three years’ imprisonment in Warsaw. He was released after two years.

View into the courtyard

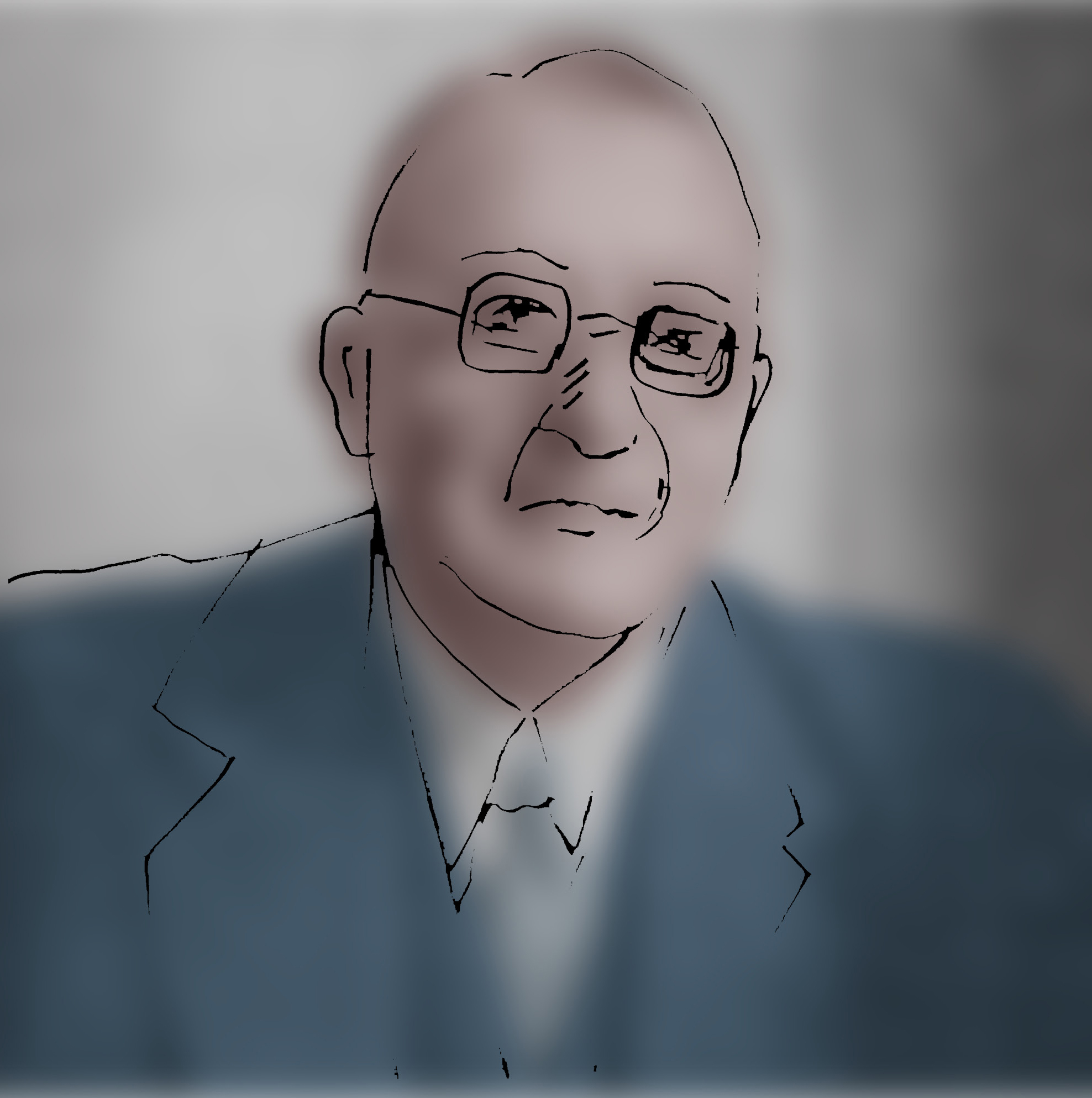

Theme box: Ernst Hagemeier (1888–1966) Manager in the age of the economic miracle

Ernst Hagemeier (1888–1966) Manager in the age of the economic miracle

Ernst Hagemeier (1888–1966) Manager im Wirtschaftswunder

Denazification proceedings, 1947/48

In November 1947, the senior public prosecutor’s office in Frankfurt dropped its investigations into Ernst Hagemeier. He had often exhibited “a humanitarian understanding of the inmates’ situation”.

Independently of that decision, denazification proceedings against him were initiated barely two months later. His lawyer had prepared thoroughly and was able to submit some 46 written testimonies to the court. The witnesses for the defence included authorized Adlerwerke signatories, simple employees, a Gestapo officer, the chairman of the works council, and even a dean. They all underscored Hagemeier’s rejection of Nazi ideology and the Nazi party NSDAP, his efforts to ensure the good care of the forced labourers, and his loyalty towards Jewish employees. Incriminating witness statements hardly played a role in the verdict. He was classified as a “Mitläufer” (“follower”).

Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main, inv. S2, no. 2216

B/w photo, later colouration

Internment camp (1946/47)

Ernst Hagemeier planned to reconstruct the Adlerwerke. On 3 August 1945, however, he was arrested by the U.S. military administration. Following initial interrogations he was transferred to the internment camp for suspected war criminals in Dachau in August 1946. He staunchly denied all responsibility for the maltreatment of forced labours. In 1947, the U.S. military administration ordered that only more major cases with clear evidence were to be pursued further. That helped Hagemeier.

He was released from the internment camp on 17 April 1947. In the court proceedings that would follow, his discharge papers with the wording “Cleared by War Crimes” served him as an important document in his exoneration strategy.

Chairman of the board of directors after 1947

No sooner had he been released in 1947 than Ernst Hagemeier returned to the Adlerwerke board of directors. There he pushed for changes in the company’s product range. The Adlerwerke abandoned automobile production and began manufacturing bicycles, motorcycles, office machines, and machine tools instead. From the present-day perspective it was a bad economic decision.

In early 1953, Hagemeier was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany for his achievements in the rebuilding of the Hessian economy. At his own request, Hagemeier resigned from his post as chairman of the board of directors in 1955. Two years later, the Adlerwerke was taken over by the Grundig company.